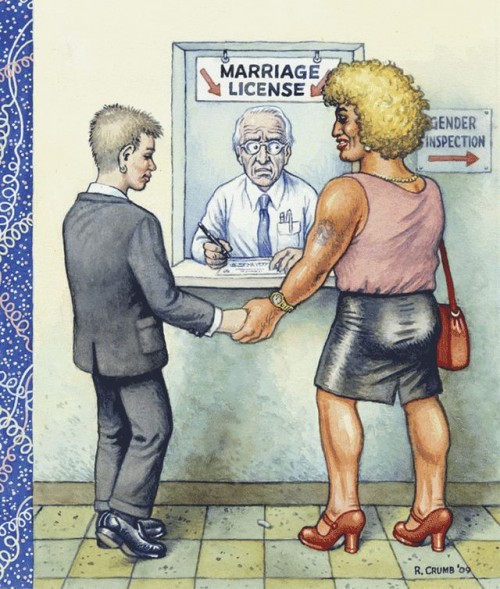

Crumb Illustration the Family That Lays Together Stays Together

Since 1978 I oasis't missed a single isue of The Comics Journal. I won't go into the many reasons for my devotion, but I'm certain many boyfriend readers will agree that ane of its niggling pleasures were the numerous lovely, often witty covers information technology deputed from some of the best cartoonists and illustrators worldwide.

Below is a pocket-sized gallery of some of my favorites…

This merry drawing by Brian Bolland for #122 graces what is is easily my favorite TCJ cover. Impeccable execution and fine humor, contrasting boozy reveller John Balderdash with tight-assed Uncle Sam. The British do often like to mock American puritanism; however the illo too comments on the welcome shake-up of U.S. comics brought well-nigh past the artists and writers of the early '80s "British Invasion". Try to detect a copy; the interviews are some of the almost entertaining you'll likely read. The Kevin O'Neill chat made me express mirth out loud.

One of those Brit invaders was Bolland's long-fourth dimension compadre David Gibbons, who truly rocked the comics scene when he and scripter Alan Moore produced the seminal series Watchmen. One of that comic'due south recurring motifs was a circular "smiley" confront bisected by a claret splatter. The above cover by Gibbons for issue 116, depicting his cartoon desk, evokes that image subliminally.

Two more than from beyond the Atlantic: #279's crisp composition past Dutch artist Joost Swarte…

…and the incomparable French draftsman Moebius in #118.

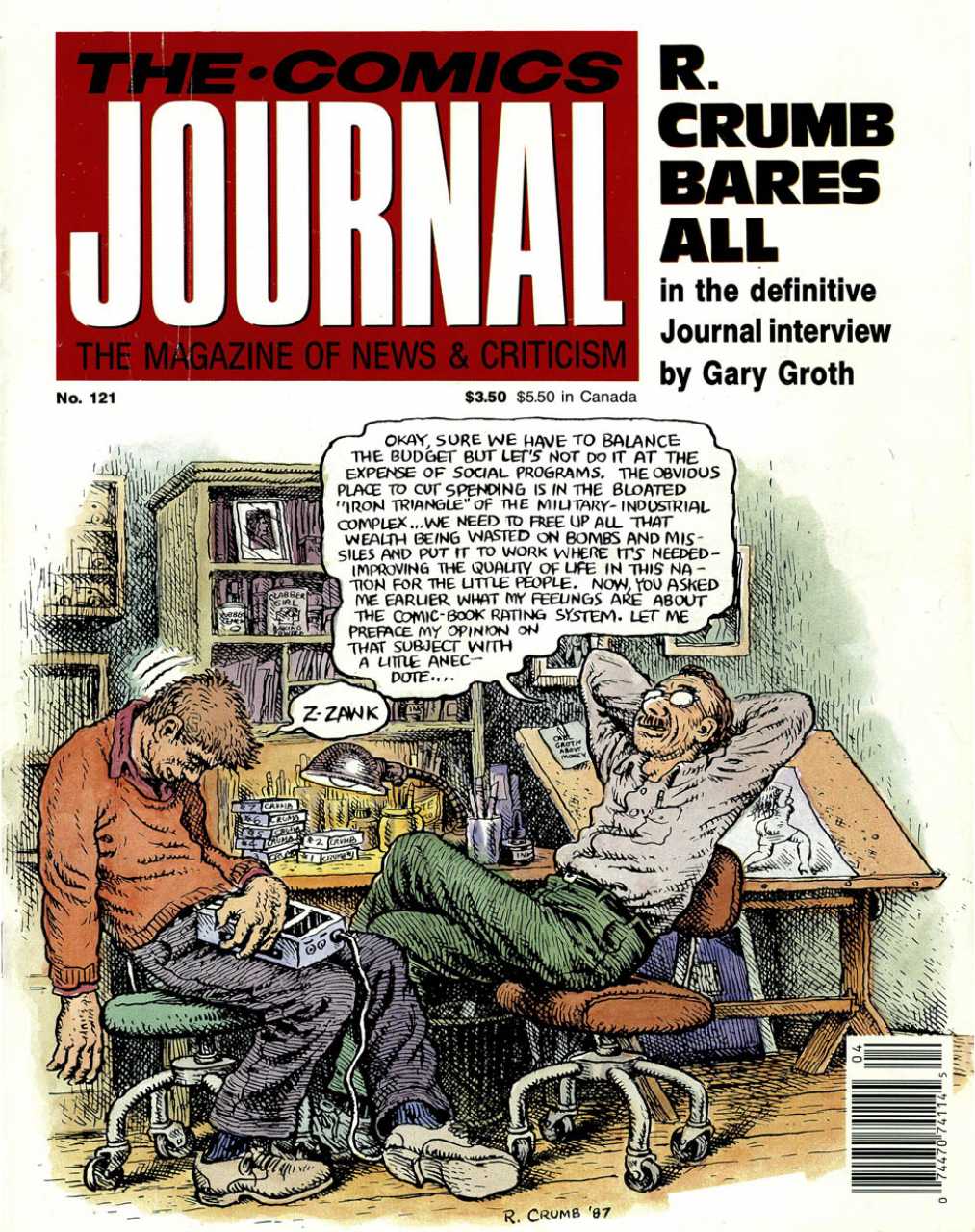

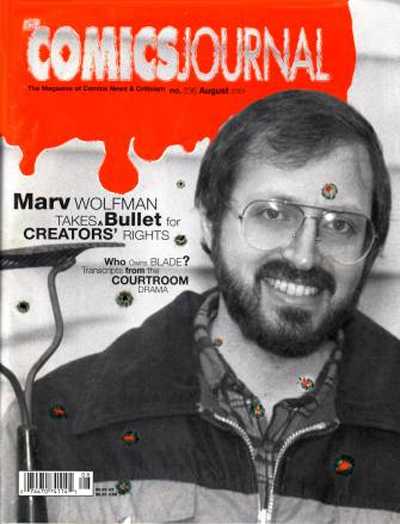

Another very funny cartoon for issue #121 by Robert Crumb. The creative person mocks his own pomposity. The chap struggling to stay awake on the left is Journal publisher/editor Gary Groth, who'south made the cover several times — ofttimes to be teased… The cover showing the interview process is a recurring theme, one that I savour. Three more than examples below:

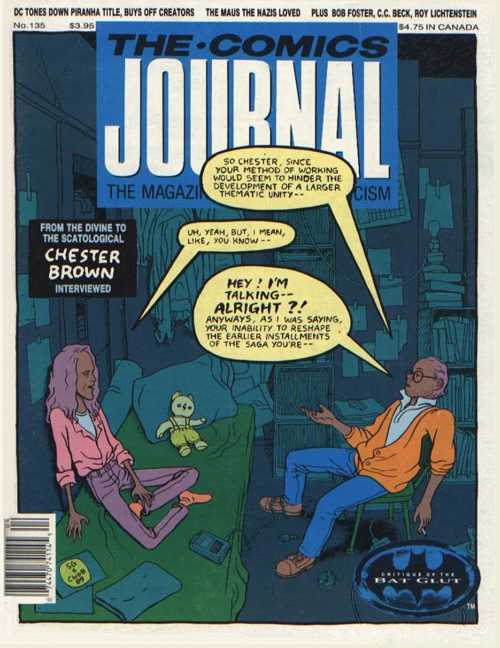

Chester Brown, who drew #135, was indeed a somewhat reticent interviewee faced with a garrulous questioner, as shown.

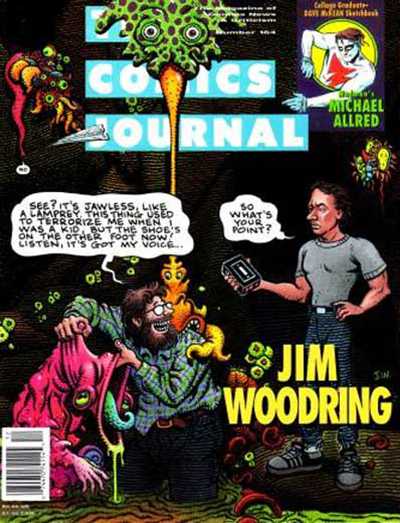

Gary Groth once again, fatigued by Jim Woodring –another self-satirising creative person…

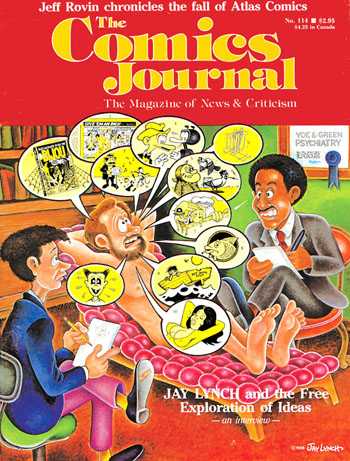

And yet some other, the clandestine comics artist Jay Lynch!

We segue to another underground classic cartoonist, the belatedly Spain Rodriguez, whose gritty urban scene with touches of fantasy encapsulates the diversity of his art.

Spain was one of the artists who illustrated the naturalistic scripts of Harvey Pekar, every bit was Nibble, who illoed this slice-of-life for #97. (That's Pekar in the blue coat, with Crumb next to him.)

And another Pekar collaborator was the main of grotesque realism Drew Friedman.

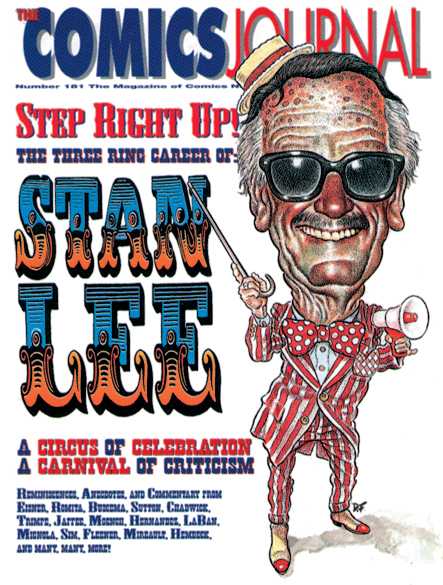

Friedman likewise contributed this caricature of writer-cum-huckster Stan Lee for #181. Now, sometimes the art direction for the covers is bluntly not up to the bodily illustration; but this fourth dimension the AD worked in impeccable harmony with the artist. Below are ii more exemplary cases of this.

A terrific character design by Mike Ploog for #274 elegantly fix off…

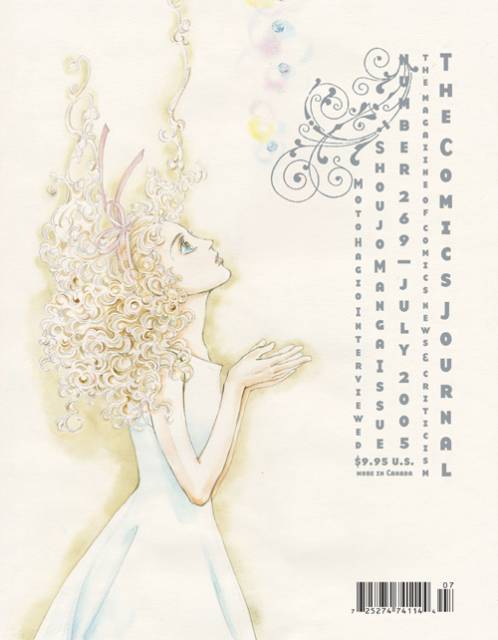

…and a lovely cartoon past Moto Hagio for #269; apologies for the light scan, merely the embrace is truly a delicate confection.

The EC comics from the '50s were an inspiration to generations of artists.

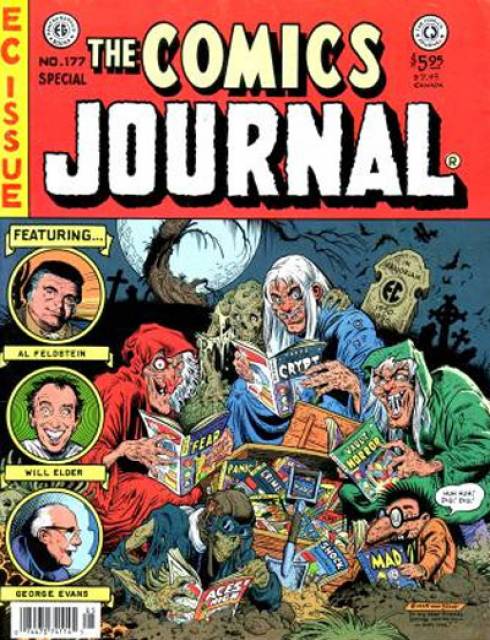

Notable among them was Bill Stout, who pastiched their cover format twice for the Journal; above, for effect 177…

…and here, for #81. Those three Journal contributors at left? The Critic Keeper is, I assume, Gary Groth; the Old Bitch is probably Marilyn Bethke, one of the virtually virulent early on writers for the mag; merely who is the Fault Keeper? Enquiring minds want to know!

Topping off this EC-themed trio: a Mad magazine pastiche by frequent Mad cover artist Kelley Freas for #225. Two of Freas' iconic characters run into here: Mad mascot Alfred E. Neumann in the blood-red spacesuit; and the Martian from Freas'historic embrace to Fredric Brown'due south comic SF novel, Martians Go Domicile. Freas is considered by some the greatest science-fiction illustrator of all.

I'm frustrated past this one. Don Simpson drew an awesome wrap-around cover for outcome 115, featuring literally dozens of comics characters from around the world. Alas, I could but detect a scan for half the cover.

Kevin Nowlan drew this Alternative Comics Cadaver Derby for #98. Apart from Fantagraphics and Final Gasp, all the publishers whose characters are hither racing off a cliff are in fact extinct: Eclipse, First, Renegade, Kitchen Sink, and Aardvark-Vanaheim…BTW, Howard Chaykin, the creator of American Flagg, stated that Nowlan's depiction of that grapheme (2nd from the right) was the best he'd always seen, including his own.

I am very fond of multi-console comics every bit covers, and higher up is a magnificent example by the mighty Frank Thorne for #280. Here the aged cartoonist, famed for his porn and cheesecake, laughs in the face of his own bloodshed: a joyful victory of Eros over Thanatos.

Another good comics-as-cover past Dan Clowes.

I simply enjoy the peacefulness of this drawing past Paul Chadwick for #221. The cross-section of snow with burrowing field mouse is a touch typical of the nature-loving artist. Its soothing blues contrast with…

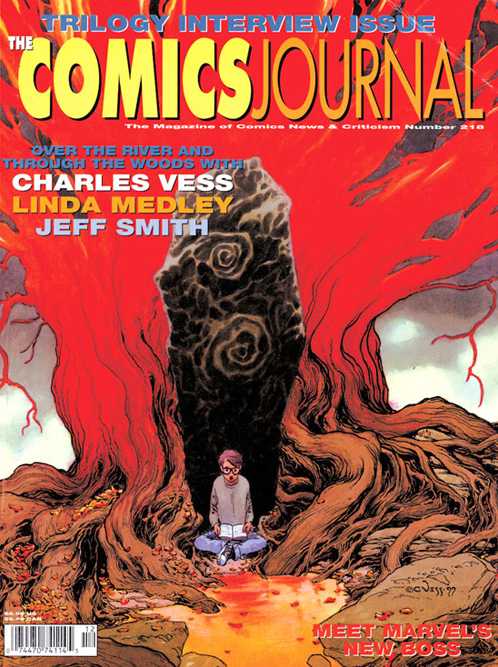

…the fiery eldritch reds of this Charles Vess illustration for #210. It's hard to etch a symetrical picture that isn't ho-hum; he pulls it off here.

Another tranquil analogy past Stephen Bissette and John Totleben. Swamp Thing meditates on a newt for #93.

Something of a fanboy guilty pleasure, this. Iii stretching superheroes — Jack Cole's Plastic Human being, Jack Kirby's Mr Fantastic, and Carmine Infantino'southward Elongated Man get tied up in knots… The artist is Dennis Fujitake, a prolific correspondent to the early Journals and the artist on Journal publisher Fantagraphics" first color comic, Dalgoda, written by Jan Strnad.

So much for attractive covers. What'south the Journal'southward ugliest cover? The tardily Kim Thompson nominated this:

I can't honestly disagree, can you?

Let's finish with a comprehend from The Comics Journal's sis publication, Amazing Heroes, past the always-inventive Bill Sienkiewicz. "Faster than a speedding bullet", indeed.

Whatever of your own favorites missing? Scan for them either at mycomicshop or at the Comic Vine.

In the start, R. Crumb created comics. I didn't know this was the Give-and-take until I went to the Comics: Philosophy & Practice conference in 2012. I just sort of causeless that Art Spiegelman had created comics. Now I know that'southward but in academia.

That conference was enormously interesting, simply two things particularly stood out to me. The first was that Spiegelman, who was billed as the keynote speaker, transformed his speech into a dialogue with a prominent professor of media. "This was going to be a talk past me just I was too daunted by the audience of fifteen or sixteen peers who were billed equally being here with me," he said. "I couldn't make myself evangelize something that's called a keynote address." This was clearly a concluding-minute change; information technology wasn't noted in the programme.

Possibly Spiegelman was just being modest, only on another level, he was absolutely correct: he was not the leader in that room. Over the course of that weekend, it wasn't Spiegelman's name that I heard praised again and again and again; it was Crumb's. It was almost equally though people took turns speaking to his influence. Equally thoughtful artists like Joe Sacco and Alison Bechdel paid him eloquent tribute, Crumb shouted devious observations from the audition like someone'southward drunken uncle. I idly wondered if he was dying.

The second interesting matter was a disagreement that Crumb had with Françoise Mouly virtually his blown cover for The New Yorker. Mouly explained why the magazine rejected the art: it felt out of touch. But this is non the critique that Crumb heard; he preferred to bandage himself as a provocateur. "I merely realized that you have this loyal readership there that is pretty fucking square," he said. "When you work for The New Yorker…you take to kind of curve whatsoever lurid qualities your work might take to fit that sort of lite, L-I-T-E [mentality]."

Characteristically, he was a real jerk about it. Merely what was almost fascinating to me in looking at the cover (which Mouly had projected onto a huge screen) was that information technology was totally impaired. It had the unique distinction of being heavy-handed without really making much sense—exactly the kind of "political" work you might expect from an artist who built an empire on drawing his dick.

It's i thing to feel agnostic towards other people'southward god; it's quite some other to observe him ridiculous. Crumb's affectations, his attitude towards women, his dim take on race—I don't intend to spend a unmarried second of this wild and precious life trying to figure out what other people run into in that. Does that mean I'll never understand comics? The reply is, simply, I don't care, but I worry that'south big-headed. And on some other level still, I feel resentful of that worry.

I find that writing, like life, is a delicate residuum of feeling worried and giving naught fucks.

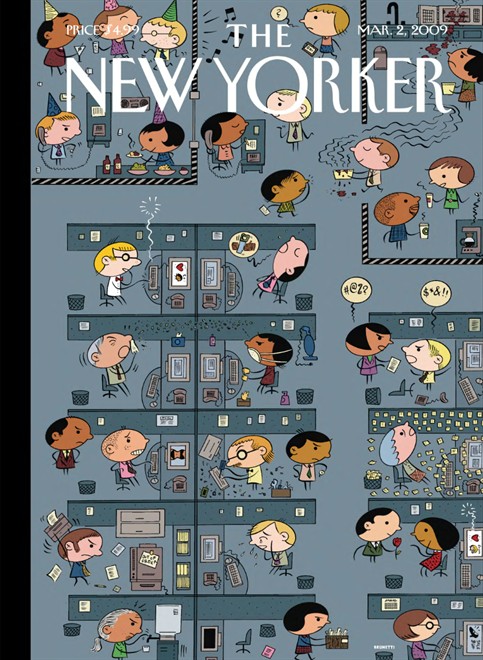

I like paradox. It's the engine that powers everything interesting. When I started reading comics in a critical capacity, I was startled by the early work of Ivan Brunetti, whose illustrations I had seen in The New Yorker and Real Unproblematic for many years. I hated Misery Loves One-act. It was nothing similar his work I knew and loved. But knowing the same man drew all of those things made me experience very hopeful about the world, where all too often people are afraid to embrace multiplicity. Now I browse every result of Real Simple hopefully for allusions to murder-suicide. This brings me great joy.

There is a certain type of discourse—or is it a full-blooded?—that is highly valued in comics crit. Names of the founding fathers (and let's confront it: it's always the fathers) are whispered with reverence as a sort of password into that clubhouse. In that location is also a tendency to value historical perspective over any give-and-take of the present. Creating a false opposition between then and now (or high and low or this and that) is often done in the name of historical preservation, but information technology's ever a thing of propagating an stance. There is no such thing as objective criticism; it is always an extension of the self and what you care nearly. There is an important distinction betwixt saying these are the things that matter and saying these are the things that thing to me.

Still, some take a cold approach. They equate getting good with growing calloused. They forget that sensitivity is a tool, not a flaw. Men who acquire to employ that tool are by and large praised. Sensitive women are crazy or inexperienced. We're confused. We OVERREACT. Or then we're told.

When I wrote the Piece that Shall Remain Nameless, I knew I'd be told all of those things. I felt a lot of dubiety. I knew it would take fire that was far more intentional than the smoke the slice itself described. I thought that speaking up was the right affair to do. Now I'm not sure. I never am.

(I give zero fucks. I give zero fucks.)

I closely read a very small amount of material, not because it was in itself momentous, or to catch anyone in a word trap, merely to explain how I felt about it, and also how I felt well-nigh something larger. The feelings were instantaneous when I read the cloth; the close reading came afterwards. In response, people closely read my writing back to me. They called it off-white, but I would argue it was non in the aforementioned spirit as the i in which I approached the project. And then information technology goes.

There's no one path to understanding. We go about information technology in unlike ways, if nosotros go most it at all. In examining an consequence from dissimilar points of view, information technology's necessary to be critical of another vantage. But it's as necessary to interrogate your own.

R. Crumb created comics, and it seems to me that comics crit was then made in his paradigm. I see his bad attitude and rude behavior all over this boondocks. I come across his petulance and his defensive posturing. I run across his unwillingness to absorb a critique. And I also encounter his growing irrelevance—mayhap nigh keenly every time some other fanboy tries to foist his opinion on the world nether the noble guise of History.

Real criticism thrives in doubt, not in certainty. In conversations about comics, there is no right and wrong. In that location is only coming correct. Under the stone of my lousy long essay, it seems to me that a few people tried. Many others came to conquer. The anxiety of it, as ever, is women's work.

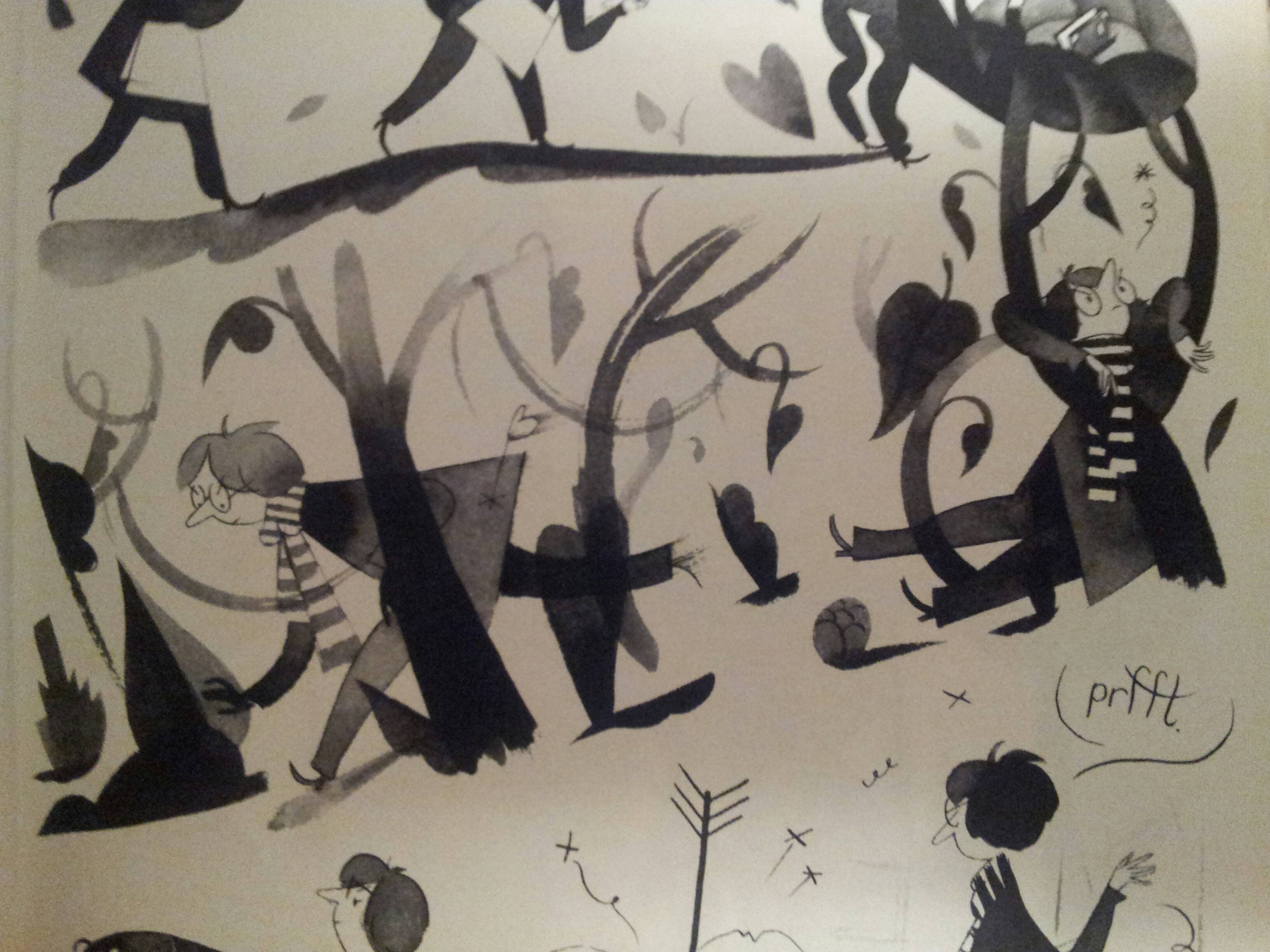

The previous contributions to our roundtable have raised important questions near Thierry Groensteen'due south approach to page layout in Comics and Narration. While a rich array of images in Adrielle Mitchell'due south mail service encouraged us to consider how frame irregularities produce significant, Roy Cook set the phase for an important conversation nearly the values comics readers aspect to different panel arrangements. Roy'southward mail service really got me thinking well-nigh the way Groensteen privileges the layout pattern of the "waffle-atomic number 26" by identifying stability, simplicity, and transparency equally cardinal attributes of the orthogonal shapes. Groensteen further conceptualizes the grid in the narrative rhythm of comics as the "basic beat" confronting which the visual and verbal elements of comics can improvise.

From this perspective, it's not difficult to see how one might characterize the grid equally "regular" or "neutral" or "invisible," but I remain troubled past the relative nature of these terms, who defines them and in what context. To complicate the issue, my first instinct was to seek out comics that delight in the wildly experimental layouts that Groensteen might observe "more sophisticated (or more hysterical)," but Adrielle's mail provides several excellent examples already. So I thought I would inquire instead about comics that use the filigree, but in unexpected means: how practise comics adapt the basic panel layout in society to stray from what Roy described equally Groensteen'south "waffle-iron fashion of truth"? When is a grid non just a grid?

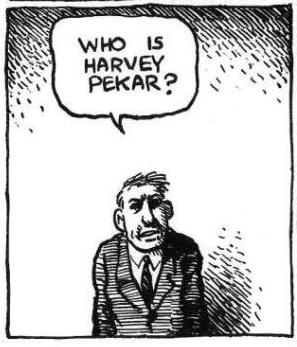

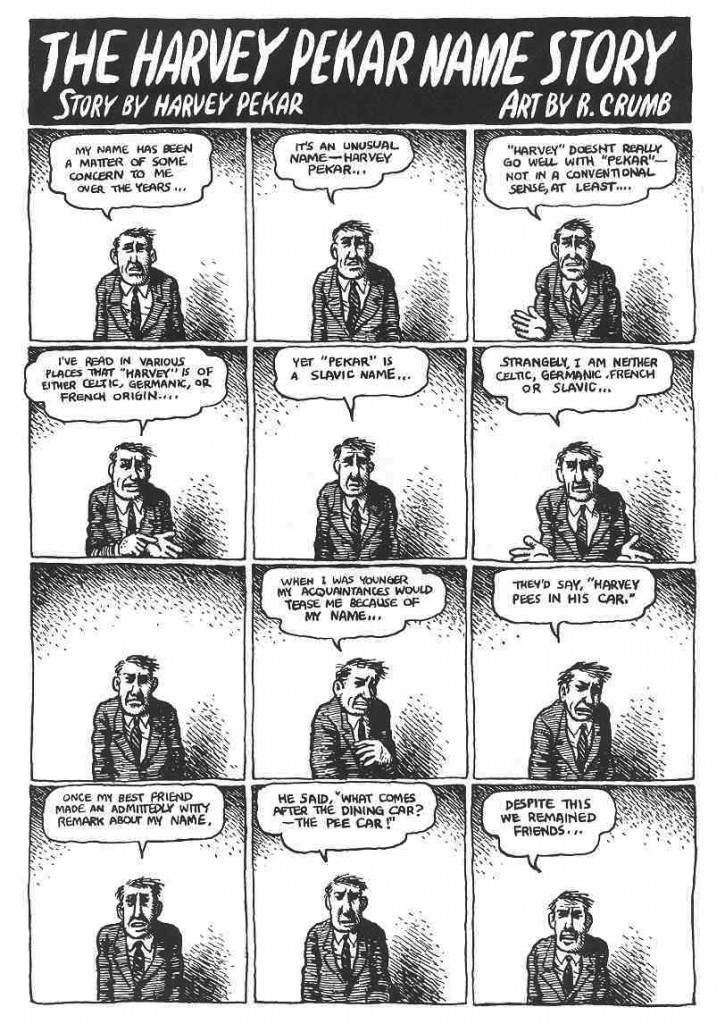

I wonder, for example, how a comic like "The Harvey Pekar Proper noun Story" fits into our agreement of frame regularity and rhythm. Though we may be inclined to brand assumptions about its uniformity at get-go glance, R. Crumb has not simply drawn 48 identical copies of the aforementioned human being in the squares of this 4-folio comic about the different Harvey Pekars listed in the phonebook.

The text varies and so too do the hand-drawn panels that reveal each frame's scratchy imperfections. The careful reader's heart becomes attune to the nuances of Harvey's expression and posture. Information technology is a "basic layout blueprint" and yet information technology has "irregularity as a common feature" (43) — a fitting contradiction for a story about Harvey Pekar's search for his own unique identity. It seems to me that a comic like this i actually exposes the illusion of neutrality by calling attention to the filigree'southward own constructedness.

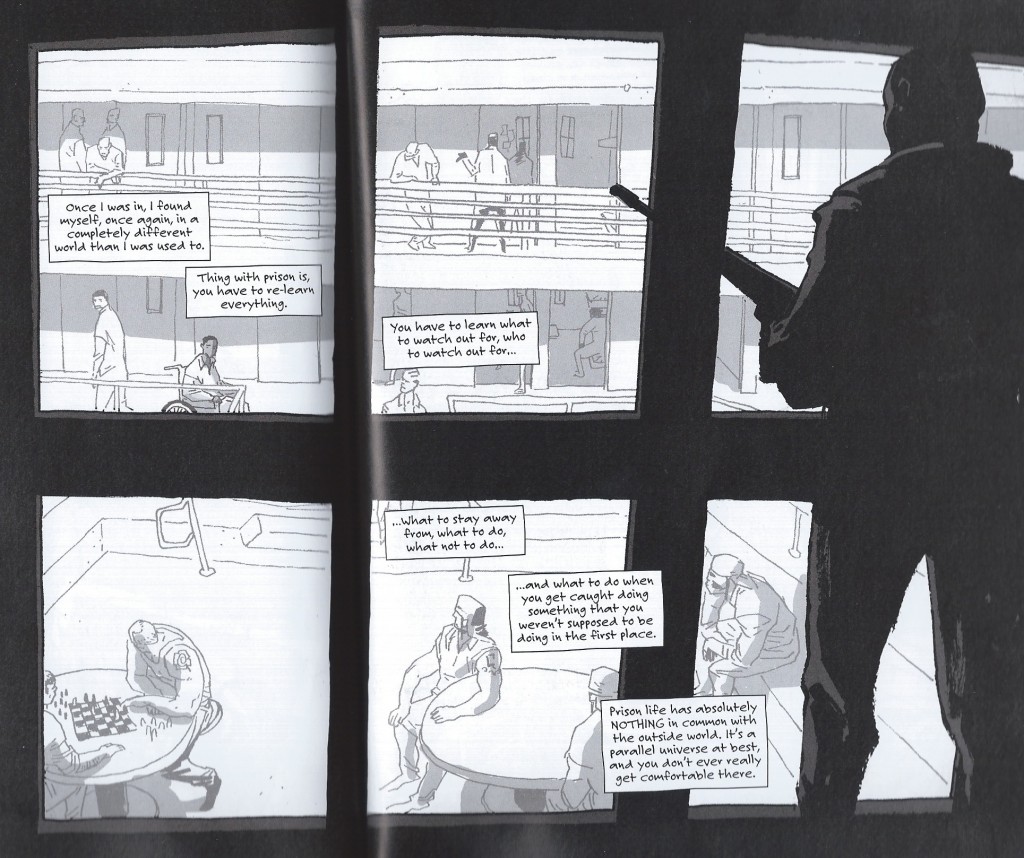

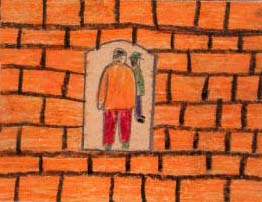

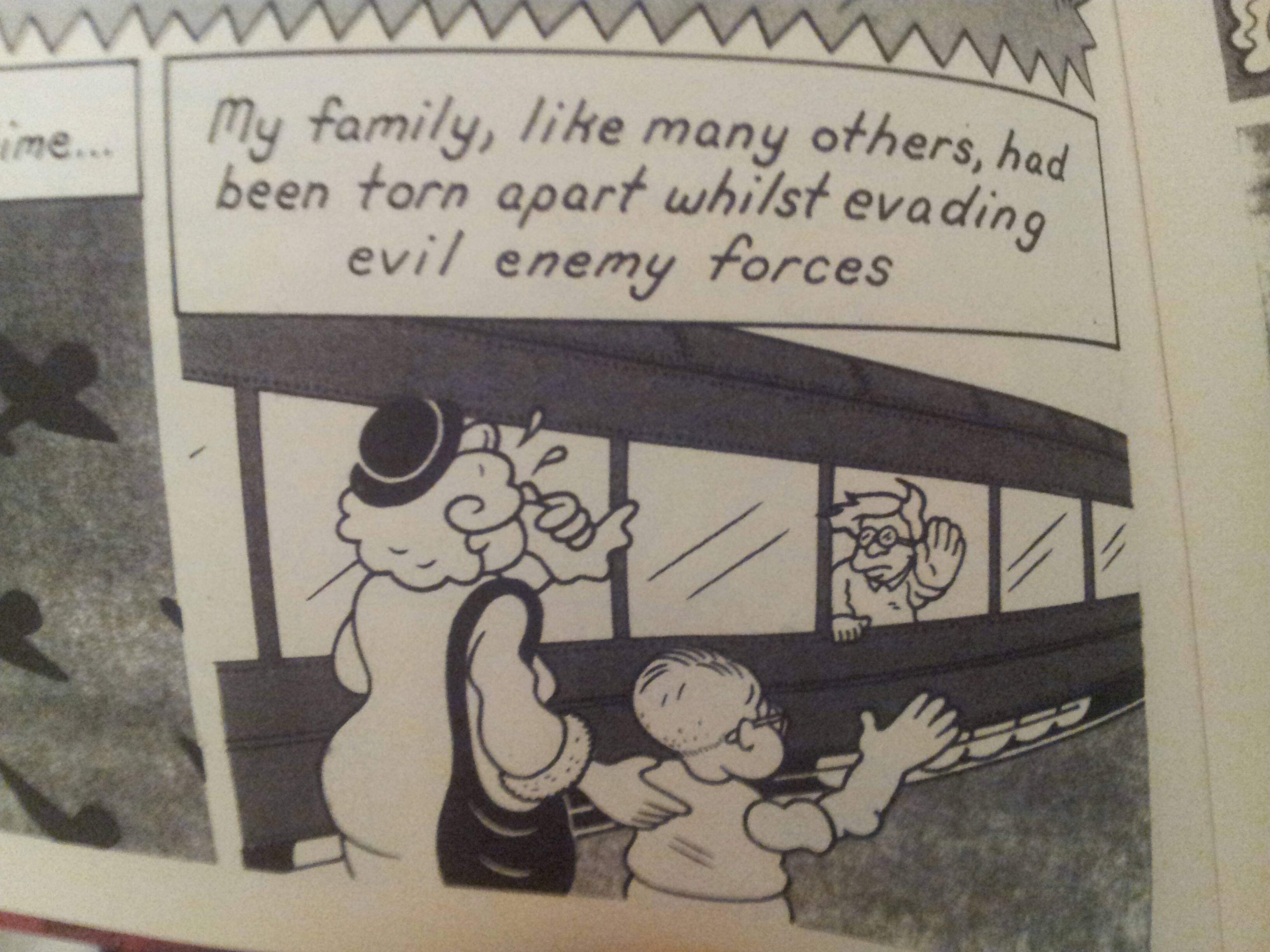

Another example that comes to mind for me is a two-page spread from Percy Carey's graphic novel memoir Sentences: The Life of Yard.F. Grimm with art by Ron Wimberly. During Carey'southward time in prison on a drug conviction, Wimberly uses the confined of the jail cell to structure the layout of the page, building barriers betwixt u.s. and the detained bodies, the narrative boxes, and the armed guards

Groensteen describes the thick borders that Chris Ware uses in Jimmy Corrigan as having "an almost carceral appearance" (48) and given the emotional constrictions of multiple generations of the Corrigan family, Ware'south panel choices assistance in the production of that pregnant. Alternatively, Sentences is a comic that has an unpredictably fluid design with layered panels and splash pages to convey the early days of hip-hop and Carey's experience with music, drugs, and violence during the 1990s. The waffle-atomic number 26 design is not the norm by any means; when the grid in a higher place appears, it actually disrupts a narrative rhythm that the writer and artist have already established. The uniformity of the panels might also be said to reflect the carceral lens that would continue to follow Carey afterwards beingness released from prison.

Is this frame neutral or invisible? How might the perspectives of these two comics help usa to reconsider the notion of the "basic panel layout" in other comics?

In 2006, four-year-erstwhile Sean Paddock suffocated in a blanket his female parent tied too tightly to cease him from getting out of bed. She's at present serving a life sentence for felony child abuse and showtime-degree murder. She was a follower of Michael Pearl'south parenting manualTo Train Upwardly a Child, which warns never to put a kid "downwardly and then allow him to get upward…. To get up is to exist on the firing line and go switched dorsum downwardly."

In 2010, 7-year-old Lydia Schatz died later on beingness beaten with a plumbing tube. Her male parent is serving a minimum of 22 years for 2nd caste murder and torture, her mother thirteen for voluntary manslaughter and unlawful corporal punishment. They were post-obit Michael Pearl'south advice: "a plumber's supply line is a adept spanking tool. You tin get it at Wal-Mart or any hardware store. Ask for a plastic, ¼ inch, supply line. They come in unlike lengths and several colors; so yous can take a designer rod to your own taste."

In 2011, 13-year-old Hana Grace-Rose Williams died of malnutrition and hypothermia in her lawn. Her father received 28 years in prison house, her female parent 37. What do you call these people? Michael Pearl, a fundamentalist pastor and founder of the non-profit organisation No Greater Joy, says they are skilful, Christian parents. "Prove that you are bigger, tougher," teaches Pearl. "Defeat him totally."

Frank Miller calls these people "Batman."

Miller and artist Jim Lee stirred up DC in 2005 with theirAll Star Batman and Robin and its portrayal of a Pearl-style Bruce Wayne abusing his own adopted child. Co-ordinate to a Sheriff's written report, the Williams deprived their adoptive daughter "of food for days at a fourth dimension and had made her slumber in a cold befouled." Batman keeps Robin in an empty cave and tells him to take hold of rats if he's hungry. If he cries, he gets slapped. When Alfred interferes by supplying the twelve-year-old with a blanket and an club of fast food, Batman threatens his butler physically.

Pearl would corroborate. "It has come to my attention," writes the evangelist, "that a vocal few are decrying our sensible application of the Biblical rod in training up our children. I express mirth at my caustic critics, for our properly spanked and trained children abound to maturity in great peace and dearest."And sure enough, Batman's tough love program rapidly transforms Dick Grayson from a whimpering orphan to a power-punching Batman Jr.

Miller is an evangelist too. His God is the Manichean kind of absolute good vs. evil, the one little Bruce Wayne prayed to when he swore "past the spirits of my expressionless parents to avenge their deaths past spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals." Miller expanded that night vision to new depths in the early xc'south withSin City—while Pearl was self-publishing his parenting manual. The D.A. who prosecuted the Shatz case chosenTo Train Upwardly A Child "truly an evil book."

In 2009, while the Schatzes were still beating their children with plastic tubing, Pearl was applying his comic book vision of good and evil to an actual comic volume titledGood and Evil. He advertises his Bible accommodation as "The Ultimate Superhero Graphic Novel!" and explains that he didn't want "typical religious fine art" simply "the traditional comic look that is so familiar all over the world." It'due south fatigued by Danny Bulanadi, a sometime Curiosity and DC artist whose 1979 Man-Affair is in my attic box of childhood comics. His 80s and 90s credits include Conan, Captain America, Blue Beetle, Hulk, Indiana Jones, Fantastic 4, and The Micronauts. After becoming a born once again Christian, Bulanadi, according to the introduction, "was not comfortable with the work he was doing and so quit." I'm non sure what exactly he was uncomfortable with, sincePracticed and Evilencapsulates the aforementioned comic volume values as most other superhero stories.

Pearl says it's "impossible to cover the entire Bible," so he selects "just that Old Testament groundwork that is pertinent"—which plainly means adding a few supervillain scenes. "The Bible," according to Pearl, "tells us God created numerous kinds of angelic beings to offer praise around his throne, merely 1 called Friction match led a third of them in rebellion." Tales of rebellious angels don't appear till the Book of Isaiah, nevertheless Pearl needs united states to know about them on page one. "But," he adds, "this is non their story."

Except information technology kinda is. We haven't gotten through the kickoff week of creation before Bulanadi's sketching evil eyes peering from the blackness of his panels. "On the sixth mean solar day," Pearl declares, "with the evil ones watching, God formed a new brute from the dust of the ground." They're there again a page later on as God is forming Eve: "Satan, the Evil One, watched." Ii more panels and Bulanadi is cartoon a bipedal lizard monster that would expect at home inTales to Astonish: "Satan hated God and wanted to destroy what God was doing, but he needed a way to communicate with Eve, and then he entered the body of a cute creature and spoke through its mouth." Pearl and Bulandi disagree nearly the adjective "beautiful," but, more importantly, Pearl disagrees with God. According to Genesis three:1, "the serpent was more crafty than whatever other beast of the field that the Lord God had made"—Friction match isn't a "beast of the field," and in that location's goose egg in the Bible suggesting he "entered" it. Just Pearl loves to play upwardly God's curvation-nemesis. "Here is promise of a hereafter battle," he tells united states of america, as Bulanadi'south lizard monster morphs into a snake. Pearl, like near comic book writers, simply wants more fight scenes.

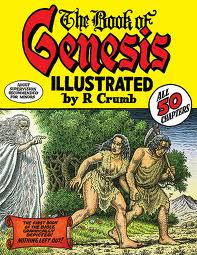

If you're looking for a faithful adaptation, I suggest Robert Crumb'sThe Volume of Genesis Illustrated. If you're likewise familiar with Crumb'sBible of Filth (information technology includes the outrageously incestuous "A Family that LAYS Together STAYS Together"), you'll presume he's out to lampoon Christianity again. The prominent comprehend alert, "Adult Supervision Recommended for Minors," doesn't help. Only y'all'd be incorrect. Crumb's drawings are respectful. Yes, he, unlike Bulanadi, forgoes conveniently angled vegetation, so there are plenty of full-frontals of Adam and Eve in the Garden, but no sex activity, but a piddling cuddling, all of it in God'south chivalrous presence.

God's long beard and robe are a platitude, only they bring out the odd thing nigh Bulanadi's God. He's invisible. The tails of his squiggly talk bubbles point at nil. When he "formed a new creature from the dust of the ground," Bulanadi draws the dust forming itself. When "God breathed his own life into the torso of dirt," Bulanadi'southward glowing cyclone of holy oxygen swirls from off-panel. But Crumb places God front and center, getting his hands dirty and embracing Adam every bit he exhales into his nostrils.

Crumb also includes all of God's words. "Every other comic volume version of the Bible I've seen," he writes, "contains passages of completely made-upward narratives and dialogue, in an attempt to streamline and 'modernize' the one-time scriptures, and still, these diverse comic book Bibles all merits to attach to the conventionalities that the Bible is 'the Word of God," or "Inspired past God," whereas I, ironically, exercise NOT…." Sure enough, go to the No Not bad Joy website and y'all'll learn that "the sixty-six books of the King James Version, naught added or deleted, constitute the whole of Scripture 'given by inspiration of God' to English speaking people." Nibble uses the King James also, merely unlike Pearl, he includes "every word of the original text."

Pearl's selectiveness privileges some ideas over others. His Genesis keeps repeating "obey" and "rebellion," the same words he emphasizes to such subversive ends inTo Railroad train Upwardly A Child. His comic volume God demands accented obedience, then the obedient Pearl demands accented obedience from children. Role of a child'due south training, explains Pearl, "is to come submissively. However, if you are just beginning to institute training on an already rebellious child . . . then use whatsoever force is necessary to bring him to bay." And this is justified because Adam's "willful and direct disobedience to God resulted in legal estrangement from God and precipitated the curse of death on Adam and all his descendants."

But don't worry—a diet of beatings and cave vermin tin fix that. Alfred may disagree, refusing to be Batman's "slave," but Robin gets with the righteous program. When you lot live in a comic volume earth of Good and Evil, choices are piece of cake. Robin's adoptive male parent, like Pearl, is a divinely pledged instrument of absolutism. And, hey, who doesn't want to exist Batman?

I ask Aline…

"Well, he is a sexist, racist, antisemitic misogynist," she says.

Does he hold? "Oh, I gauge all that stuff is in me, certain. I wouldn't say I'm an out and out racist or proud or amused past the idea of racism simply we all grew up in this culture…[…]…Those things are complex, y'know. They were as much nigh what was going on inside white people as their mental attitude to blackness people. I liked the idea when I was doing that stuff of making things that looked as if they were one matter but were actually something else."

* * *

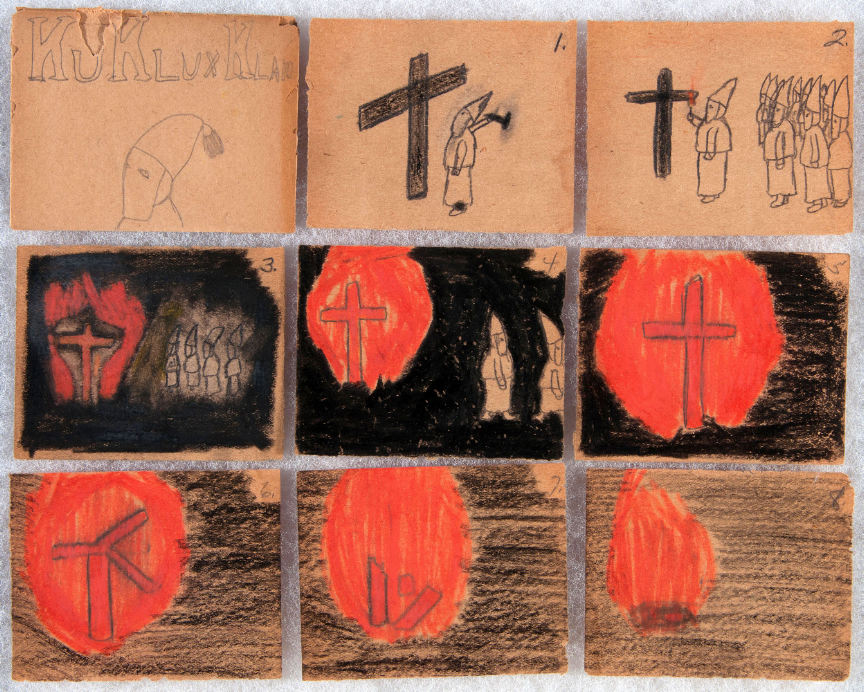

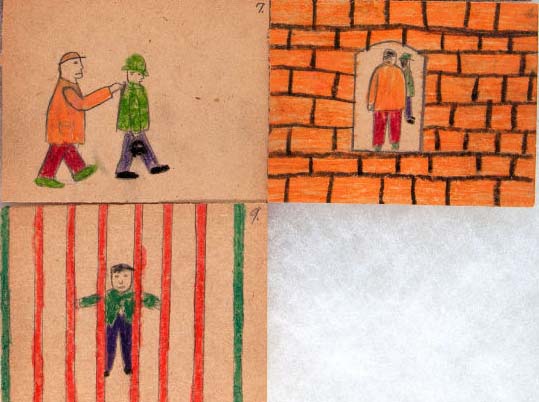

The outset comic (c. 1920) by the "last" outsider cartoonist is morally ambiguous.

The creative person's name is Russel Deiner and the comic is presented in an envelope "made of the same folded and glued paper" every bit the drawings. Each envelope is crowned with a portrait of a Klansman and the title "Ku Klux Klan." Their similarity with the comics of fandom practise not end in that location. Each is stamped with a mark of ownership and authorship, as would be done by any self-satisfied artist.

The comic itself is almost subdued in its technical transcription if non facility.

The members of the Ku Klux Klan congregate to build a cross and burn down it in the class of 8 panels. The wooden planks which make up the cantankerous are depicted studiously only amateurishly in two dimensions as opposed to the attempt at depth in the depiction of the assembled Klansmen in the second panel. There is a fitful interest in perspective. Information technology seems of secondary business organization.

The atmosphere here is not one of fearfulness merely of fascination—a deep enchantment with the lighting of the cross and its illumination of the encroaching darkness. Everything suggests an artist engaged in an try to record his own testimony or participation in an result which began in the moderate light of dusk before catastrophe in early dawn; the blank backgrounds shifting from the white low-cal of blank brown paper to the light crayon marks of one-half-daylight. The sixth panel captures the moment of disruption, when the supports finally break through and the cross crumbles to a heap of called-for shards earlier wasting to embers in the final console.

A "true" story perhaps. Or could this scene be a piece of work of solemn imagination, the work of someone recording an event every bit one would a nativity scene during a commemoration of the Advent?

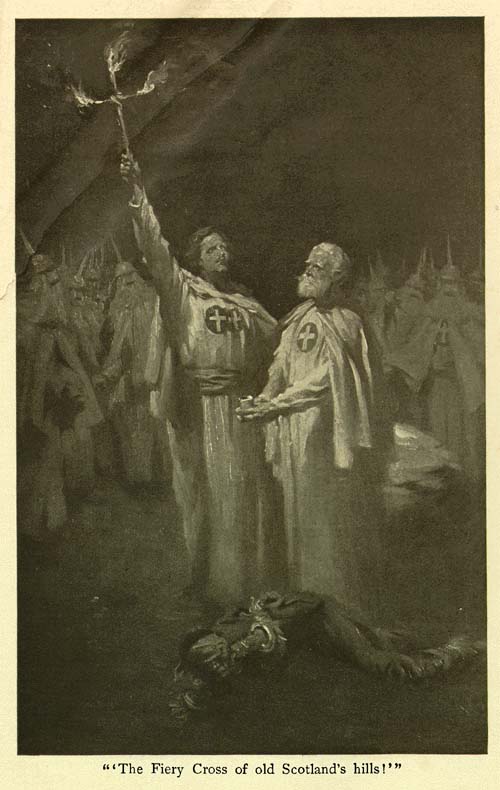

Arthur Keller's picture of two Klansmen (from The Clansman) standing erect above a fallen black victim is presumably imagined just much more specific in its motivation.

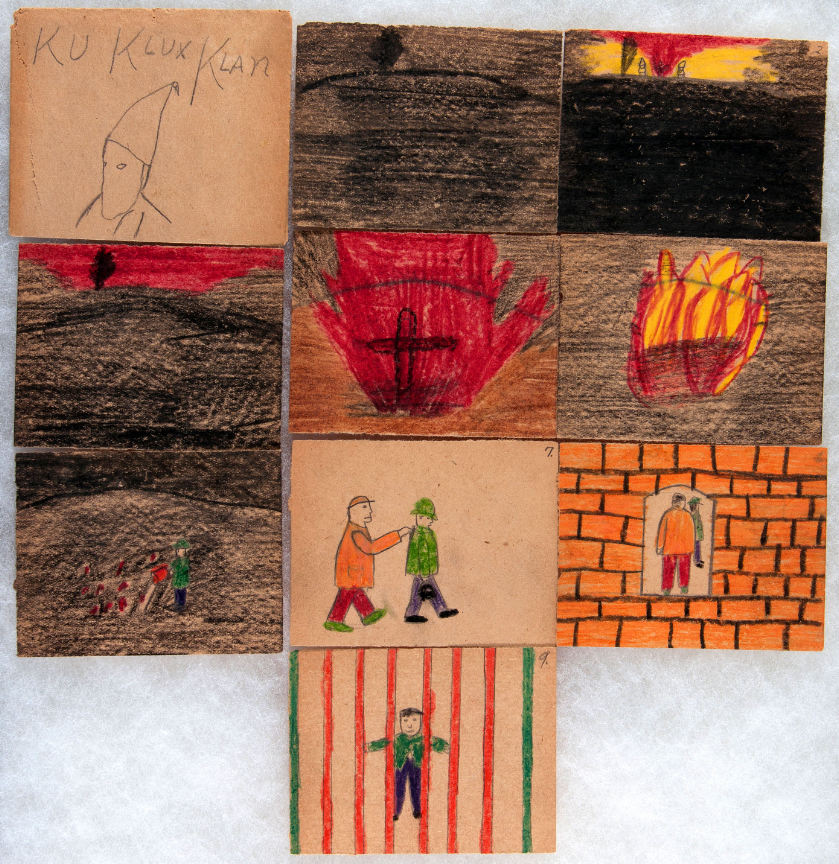

The second story by the "last" outsider artist is more studied in its appreciation of the act of burning crosses.

Much more than in the first comic, it suggests above average powers of observation, beginning first with the yellowish flames of initial combustion before simulating the diffuse low-cal of the fire in the crimson night heaven. Flames similar a geyser of blood cascade along from the redeeming article of the cross.

The members of the Klan are largely absent, ii shrouded figures seen considering the cantankerous in the 2nd panel, standing mute and inactive, a testament to the (falsely) avowed purpose of the called-for cross as noted in Thomas F. Dixon, Jr.'s The Clansman and D. W. Griffith'southward The Nascency of a Nation—a telephone call to arms.

Absent of course are the targets of this cantankerous burning. They lie at the edge of darkness, quite unseen, perhaps looking defiantly out at this pageantry similar the artist, charting the progress of the ceremony and its denouement. Perhaps cowering in their beds. Perhaps a mass of tangled lines similar the mangled heap of brush strokes at the lesser of Keller's infamous analogy.

Then the burn down is doused past a human being dressed in green and the same man sent to prison.

A seemingly innocuous act rewarded with incarceration.

The man is unhooded, perhaps acting against the will of his neighbors and disrupting the carefully orchestrated festivities. Or is this man dressed in light-green a Klansman, taken forcibly to a brick-lined labyrinth where he smiles placidly back at united states of america with the satisfaction of a chore well done—the Minotaur in his lair. Is the man in dark-green the artist himself?

The auction description for these two items is considerably less cryptic:

"As a child of about six, Russel Deiner attended Klan rallies with his father and the scenes he witnessed inspired his child-like, but artful, renditions of what he saw. Equally an adult he was an influential member in his local Klan."

Thus casting aside all notions of moral enigma.

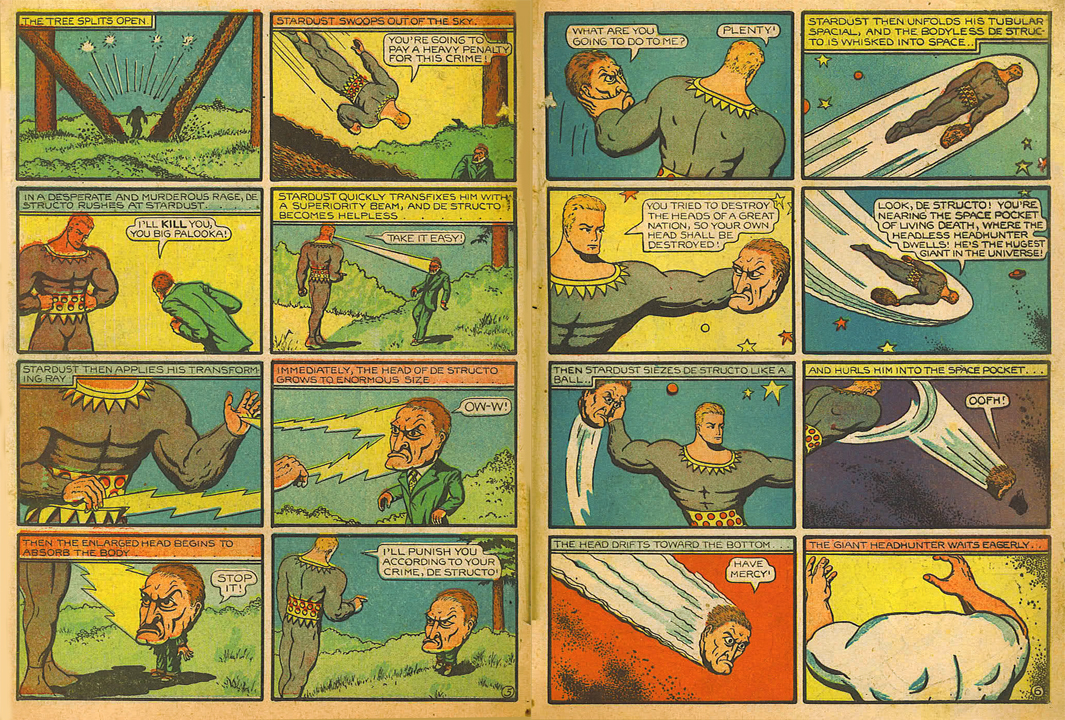

The alcoholic and abusive Fletcher Hanks, Sr. (Stardust, Fantomah) was another outsider of sorts, a neurotic cartooning expert who produced eccentric comics similarly "free" of dubious intentions. Strengthened by biography, the comics have become products of a diseased mind interested in promulgating the concepts of terror, totalitarianism, death, and eternal punishment to his young readers—this in one case acceptable face of fascism since displaced in our more enlightened times by the charismatic and self-sacrificing leadership of the wealthy vigilante superhero.

Hanks' fantasy of justice is transposed to an earthly reality in Deiner's Klan comics—an adventure in vigilantism which ends in pleasing imprisonment. Some readers will find in the 8th image of Deiner's tale a portal into the dungeon of his mind; the panels of the comic forming windows into a self-contained reality.

These panels were hung backside a "country store way drinking glass case…with other childhood memories such every bit jacks, marbles and a cap-gun." The nostalgia of the true outsider; as uninhibited as any brave truthsayer and a premonition not only of the anti-Catholicism and xenophobia of Jack T. Chick just besides of the tireless gnawing and prodding of the undergrounds and their adherents. Russel Deiner was the "showtime" outsider cartoonist; he was the "terminal" outsider cartoonist.

The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

Because comics in context does not hateful simply considering them in the context of social, political, or ethical concerns, but also considering them in the context of cultural relevance, that is, considering them in the context of a gear up of broader aesthetic developments. Because comics in context, from this perspective, is simply wondering what a given comic adds to the "conversation". Of course we're all expert post-modernists circular these parts, and nosotros don't purchase into the notion of cultural "narrative" every bit a properly unifying concept. Whether we think we live in "Tardily Capitalism" or that we've "Revealed an Essential Emptiness" or we think that we "Respect the Play of Divergence" or that "People just similar dissimilar shit, and, y'all know, anybody has their ain opinion, and so only leave me alone to practice what I want, and anyway, what are yous, a fucking conscience/fascist/communist?" nosotros tin all heartily agree (with grin tolerance all around) that there is no unquestionable benchmark for whether or not a cultural production is worth our time/coin. In that light, considering comics in terms of their context, that is, in terms of their relevance, is to consider them in terms of a close reading that takes into business relationship what they do within the vocabulary of the texts that have influenced them. Information technology's a Bloomian stance, sure, only it'southward also minimalist and generous. Information technology acknowledges that there needs to be some context to an object of art for it to even qualify as evaluable (or able to be experienced at all) and it extends a helping hand to the work past saying that the context of the work is context plenty.

With this sufficiently vague cultural program in listen, I went into Forbidden Planet by Union Square and searched badly for new "Pocket-size Printing" comics on the little shelves that wouldn't make me cry later on I realized that I had spent upward of five dollars on each of them. I shot for visuals that looked dynamic or unique, considering that most of what was on offer looked similar a bunch of silly and ugly little people standing around apartments with speech bubbles floating above their heads. I don't have Santoro money, so I only bought a couple books for this review. It wasn't scientific, it wasn't rigorous, information technology wasn't fifty-fifty especially practical, but I thought it was as close equally I could become to random while withal attempting to not experience deep regret later. As we'll come across, I wasn't successful.

ALAMO VALUE PLUS Rusty Jordan from Revival House Press

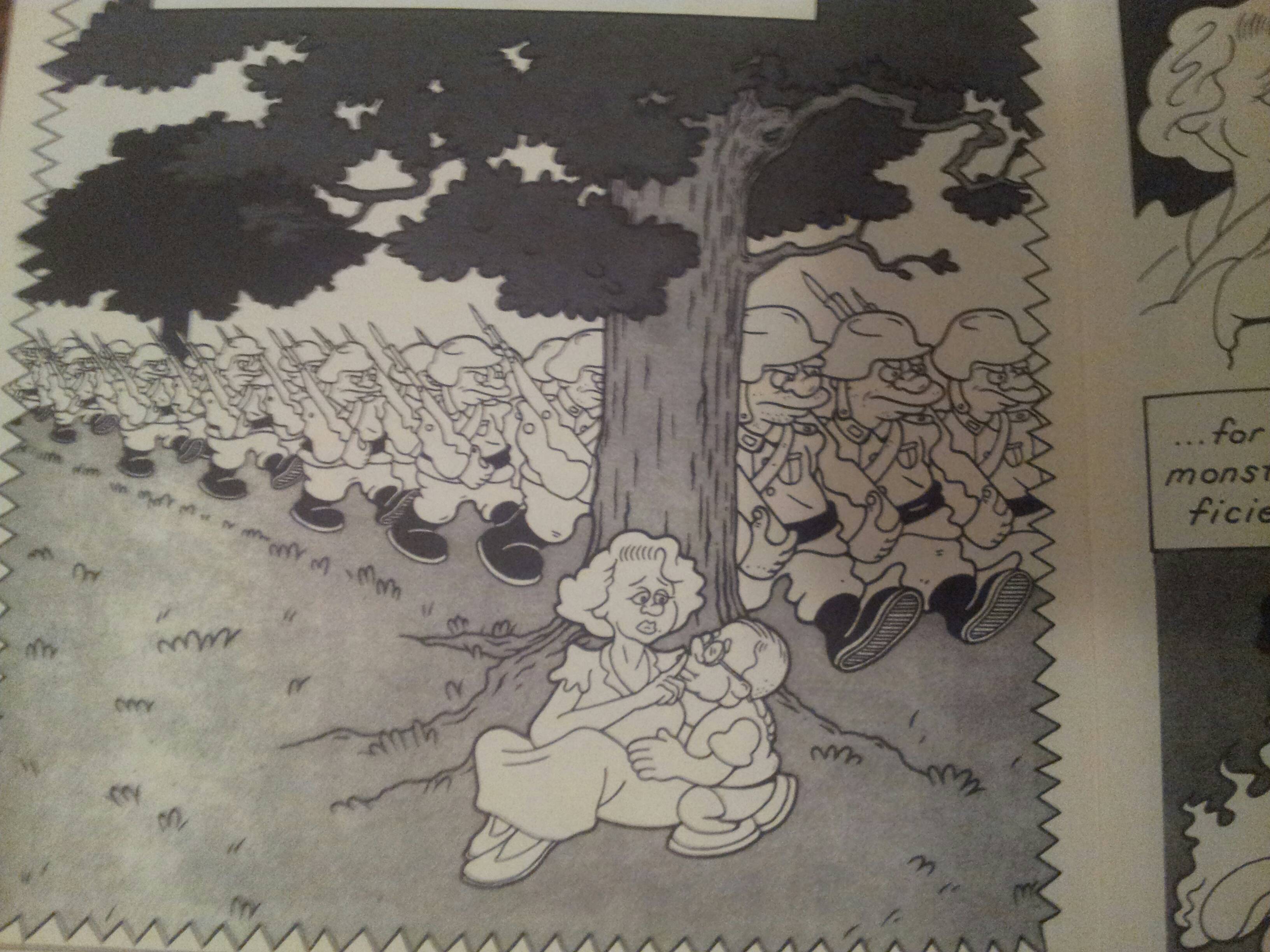

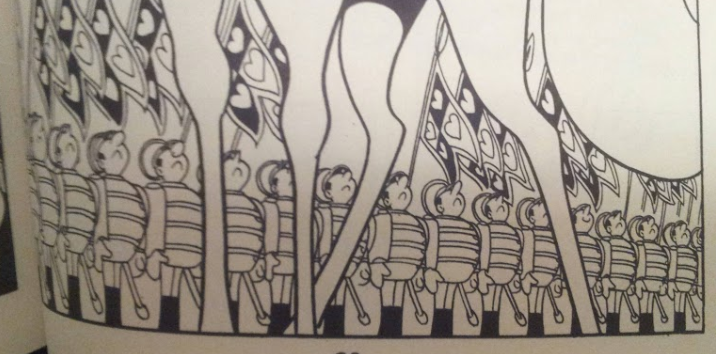

Rusty Jordan'southward aesthetic is a mix of Tezuka and the Groening workshop with spruces of Crumb and Mike Estimate thrown in. From Tezuka, he borrows a certain Disney sensibility for repetition and caricature of form.

Jordan and Tezuka draw uniformed men. Annotation the classical cartoon repetition. Neither is afraid of

typology when it comes to stock characters.

From Groening, he takes faces and physicality.

Jordan character and obvious Groening precursor.

Notice the reference in lips, eyes, and nose.

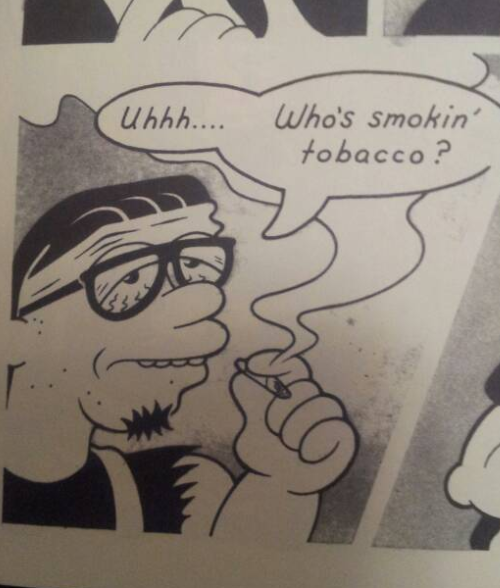

From Nibble, he takes a certain penchant for ugliness (every bit so many exercise.)

Jordan and (fairly unexaggerated) Nibble.

Notation the ugly, vacant molding of the characters. Griffith is also nowadays.

Information technology's charming, but the charm wears away quickly. The characters are boring; the protagonist, Baldemar, is an onetime man straight out of Groening cartoon, and the other ii characters are ears for his crypto-WWII tale that isn't even brave enough to characterization its antagonists Nazis.

Evil Empire. More Groening.

Just keeping in mind our disquisitional calendar, does Alamo Value Plus provide united states with annihilation that isn't already on offer in the source material? The answer is no. The corporate workshop that produces Groening scripts is cleverer (fifty-fifty today), Tezuka books are more perfect executions of sterile formalism, and Crumb, for all of his shitty sensibilities, at least has the decency to put his ugliness on display. The story is plodding and the "action" sequences are wooden.

Not very dynamic at all. Warner Brothers and Groening all over.

If y'all wanted to read a WWII volume, Spiegelman still towers in the background. Alamo Value Plus is a "nursery rhyme" book; it'southward there to remind usa of all the comfortingly familiar stories that information technology's derived from. This is result #ane. I'm not interested in reading issue #2.

PICNIC RUINED by Roman Muradov from Retrofit Comics

Muradov reminds united states that his character is well read and insecure on every folio. His characters float around with a long legged and sketchy bourgeois wispiness that I know best from Joann Sfar.

Muradov and Sfar.

Wide eyes, narrow bodies, light bear on.

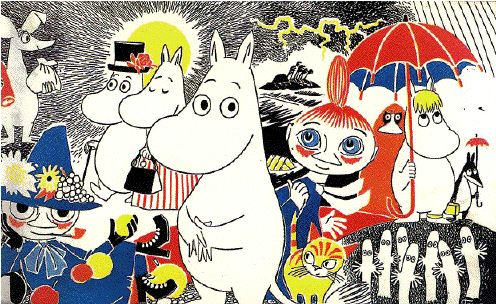

Jansson is explicitly referenced, and it's not difficult to descry her rubber and polite influence on the book.

Muradov's characters and Moomins. Plain, wispy, and vacant.

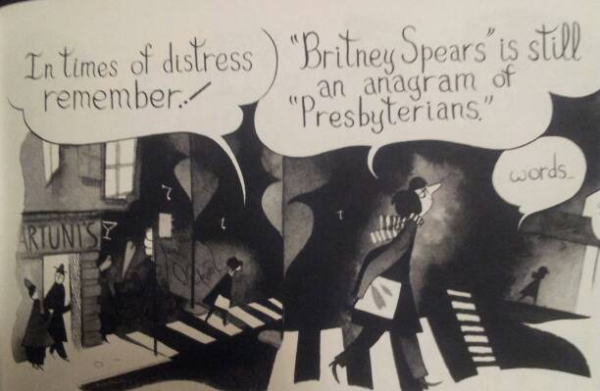

Is the book pretentious? I don't apply the give-and-take, myself, only it does betray a certain over-education. It experiments with styles taken from fine art and literature, from Beckett to Nabokov, from Klee to Picasso, thrown together in a sequence that's supposed to convey how the "protagonist" of his volume is haunted by an overflow of words that overwhelms and distorts him.

It'southward the 60's again and language writes identities.

You remember terminal calendar month, when yous went to the museum?

Then does Muradov.

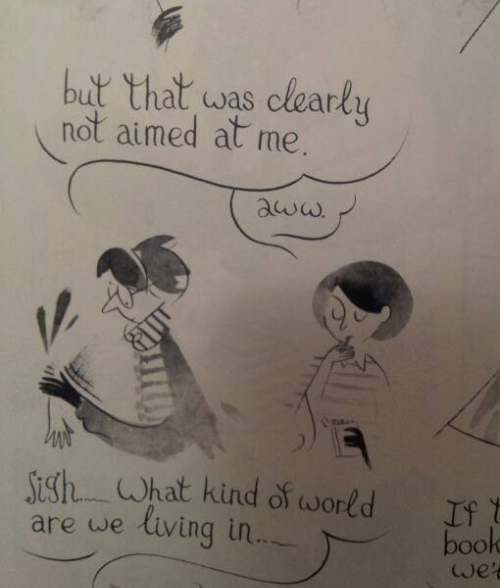

Merely underneath is a wistfulness and loss of direction that demonstrates the damp humanism behind the experimentation. All throughout the book Muradov is worried that it will come off as a masturbatory whine, including in a sequence where the protagonist talks to his shadow most how pathetic he is.

I will die happy if I never read or hear another awkward

and "funny" displacement of responsibility.

The book has nil at stake but its own round insecurities. Its most beautiful moments are expressions of the sheer emptiness of its content, but, tragically, they are undermined by its alternation between simpering cocky-consciousness and self-satisfied intellectualism.

Hearing people say this kind of shit unremarkably drives me crazy.

Reading this makes you recall why you didn't hang out with the English majors in college (ya zinged, English majors, what about it).

Let's return to our disquisitional program again; does information technology add to the discussion that it takes part in? It adds almost equally much to its illustrious forebears every bit a poetry jam adds to Crane. The visuals are beautiful at times (if you sympathise the references), only once you've read it you never take to pick it upwardly again. Possibly go back and pick up Vampire Loves or, if yous're feeling quondam, some Wodehouse.

You lot definitely, definitely are.

These comics are inoffensive. They are stable and irksome narrative and aesthetic statements. Simply if we consider the role that they play in their context, they're unproblematic placeholders. They're echoes of their source fabric and repositories for the bear on that we take reserved for formative cartoons or the feeling of being in art history form. By sticking to affective scripts, they don't even chance affective. There's no challenge or development hither. In that location's just a lot of pleasant memories and reminders that there are people out at that place that feel just similar you.

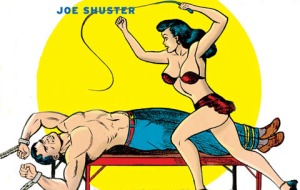

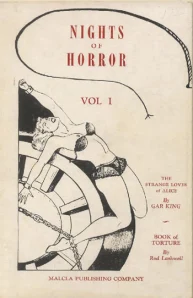

Of all the images to characteristic in this month's review of Brad Ricca'southSuper Boys, The New York Times went with one of "the kinky illustrations Shuster was reduced to doing for sleazy magazines in the mid-1950s," specifically one that, co-ordinate to editor Peter Keepnews, "looks for all the world like Lois Lane preparing to whip a trussed-up Superman."

Craig Yoe had the same idea, choosing an fifty-fifty more than overt image for the cover of Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman's Co-Creator Joe Shuster: Lois in loftier heels and underwear non preparing but full-on whipping a chained and bare-chested Clark. The Man of Steel shattered identical chains on Action Comics every month, but this Shuster illustration is working toward a very dissimilar climax.

Yoe's title is a scrap of a dodge though, and Keepnews' "kinky" is no amend. Yoe reproduces Shuster'southward 1954 illustrations for Nights of Horror, a typo-strewn black and white cranked out of Shuster's neighbour's basement, but different virtually anything else related to superheroes, this is not "Fetish Art." Zorro dressing up in a mask and cape to keep his sword cock? That's a fetish. Hooded men assaulting leap and weeping women? Frederic Wertham termed it "pornographic horror literature." I telephone call information technology rape and torture.

Craig Yoe is less coy between the covers: "These BDSM (bondage-discipline say-so-submission sadism-masochism) tales were an equal opportunity employer. Women were tied upward, whipped, and spanked, simply could eagerly be the tie-ers, whippers, and spankers, too."

Well, not exactly "equal."

Of Shuster's 108 illustrations, I count seventy-ane that depict women dominated by men. The opposite occurs ix times. Add together some other ix scenes of women dominating women for a g full of eighty female victims. Shuster draws simply 1 incident of a man dominating another man (with a woman equally the primary focus, and so the men are non—gasp!— a homoerotic pairing) for a total of x victimized men. Bank check my math, but an eighth is a lot less than "equal."

Most common torture device: a whip. Eighteen of the twenty-two appearances are used against women. Other devices used to torture women (in alphabetical order): air hose, alligator pit, ball and chain, cactus, chains, corset, electrical wire, fingernails, gun, hairbrush, hot poker, hypodermic needle, iron maiden, knife, paddle, paddle machine, spiked bed, spiked gloves, switch, and water hose. Boosted techniques to dominate women: champagne, hypnotism, marijuana, opium, and polygamy.

Men are whipped, spanked, paddled, clubbed, and one anticipates the removal of a toe. Iii more than display submission by kissing a adult female's shoe, kneeling with a tiny chain attached to his ear, and (my favorite) serving a adult female breakfast in bed.

The nudity is almost exclusively female. Merely four illustrations feature clothed women. Another ten reveal partially exposed underwear, unremarkably from a forcibly raised dress hem. Some 70-1 (past far the standard) are women in nearly identical see-through bras, panties and those mid-thigh pantyhose and garter belt contraptions I've never really understood. The remaining twenty-iii or so feature full or partial nudity, which ordinarily means exposed breasts, but occasionally buttocks, and very rarely a vaguely drawn crotch. So vague, in fact, as to seem sexless. (Women were not, to the best of my very limited my cognition, shaving their pudenda in the mid-50s).

The one image of full male person nudity is besides oddly sexless—or at least gravity-defying. The more than agonizing anatomical features are the women's freakishly tiny easily and anxiety. And their high-heels which appear to be permanent growths of their otherwise naked bodies.

Stan Lee (he wrote Yoe's introduction) looks at these pictures and sees a "disillusioned and desperate" Joe Shuster "forced to accept commissions to draw what amounted to S&M erotic horror books." Although the unemployed Shuster was financially drastic in 1954, his arrangement with Nights of Horror was sounder than his one with DC Comics.

He was paid $100 for each of Nights of Horrors upshot, for a full of $1800. Less than xx years earlier, his bosses at DC had written him a check for $130, which he split with his partner Jerry Siegel. That was in exchange for the permanent, multi-million dollar rights to Superman. Shuster drew an average of half-dozen illustrations for each Nights of Horror. That's a page rate of only over $16. He and Siegel were splitting $10 a page back in 1938. DC grudgingly raised information technology $15 when the Action Comics spin-off Superman sold 900,000 copies the following year. Nights of Horror boasted a print run of only 1,000, including the 2,650 backlog confiscated in a book store police raid.

Past any accounting organization, Nights of Horror was a far more than financially upstanding employer than DC.

As far as disillusionment?

Shuster's Nights of Horror illustrations are not hack piece of work. He'd didn't doodle a one-half dozen one-half-hearted sketches in commutation for that week's grocery money. Despite his failing eyesight (what finally pushed him out of comic books in the late 40s), these pages have been pored over. The particular is at times lovingly and so disturbingly precise—reminiscent of Robert Crumb's ain obsessively rendered female figures of the following decades. The all-time here easily exceeds the rawer cloth he rushed off for Action Comics. Joe was getting more out of Nights of Horror than a paycheck.

I don't care to imagine the nuances of Shuster's sexual life, simply I will guess that information technology was primarily a lonely activity. Yoe documents his preference for tall women (he was short), and his brief spousal relationship to a one-time Vegas showgirl in 1975 (they expect the same peak in their wedding photo). Superman provided his best option-upwards lines. According to biographer Gerard Jones (I haven't read Ricca yet), he would hang out at soda fountains and hand girls (the alpine ones presumably) sketches of his Man of Steel before asking them out. At least one fifteen-year-sometime said yes. Shuster was 25 at the time.

He was forty in 1954, and working lone. His studio of assistants dispersed after he and Siegel lost their lawsuit against DC in 1948. Nights of Horror was some of the simply art he'd sold since Superman. Although non paneled similar a comic book, the illustrations are oft sequential and draw narrative movement. 2 sequences conclude with heroic rescues of female victims by Superman-similar saviors. A sadistic film producer collapses from a detective'south bullet, and a bearded cult leader succumbs to a punch on the jaw. Only one adult female defends herself. She rushes at her captor with a pocketknife and seems to have the upper hand—briefly. She'due south bound as he whips her on the next page.

I'1000 going out on a limb here and guessing that Shuster did not collaborate with a model for these illustrations. The stock repetition of body blazon and undergarments suggests an internal, arcadian projection, one with rounder hips and thighs than whatever of today's anorexic supermodels. But fifty-fifty when a live human being posed in front of his canvas, Shuster always saw what he wanted to meet. A teenaged Jolan Kovacs answered his 1935 advertizement for a model in the Cleveland Patently Dealer. He wanted to practice his Lois Lane sketches before retooling Superman for a new circular of newspaper syndication submissions. Kovacs couldn't fill up out her sister's baggy swimsuit, merely Shuster's sketches do not share the shortcoming. The picture of Crimson Pimpernel extra Merle Oberon in his caput was bigger than the breathing woman before his eyes.

That didn't stop him from request Kovacs out on a date. Zilch much came of information technology then or ten years after when he asked her to the National Cartoonists Society'southward costume ball. She wanted to come every bit Lois Lane, but Shuster and Siegel were in the process of losing their lawsuit. But Joanne (she changed her proper noun for her modeling career) and Jerry (he attended the ball too) were very happy to see each other again. A few months later they were married. It was a City Hall upshot, so Shuster didn't have to stand up and mumble through a all-time human being's toast. Six years after the anniversary, Joe and his Superman partner were done with each other, and Joe was drawing S&K for his neighbor's underground porn pulps.

I tin can identify only six of the 108 illustrations that draw scenes of consensual sex. (Telephone call me Puritanical, but I am eliminating the reefer-smoking Jimmy Olsen in the early stages of pot-fostered date rape.) Of the half dozen, two are heterosexual, and four lesbian. In that location are twice as many lesbian images of women dominating other women, only fifty-fifty in those the content is less violent than elsewhere. Nights of Horror lesbians tend to spank with hairbrushes and blank hands rather than whips or switches.

The lesbian imagery is, of class, for male consumption. Which apparently eliminates the demand for other reader-titillating taboos. Twice the girl-on-daughter action is interrupted by a man bursting through the girls' airtight door—the thinly bearded desire of the perceived reader.

Fifty-fifty when the male person presence isn't literalized, Nights of Horror foregrounds its voyeurism. Simply one page in the collection depicts a lone figure, and she'due south not preening just for her mirror. Other pages are more than overt: an center in a peep-hole, a man leering through a window, a grinning boy at the corner of the frame watching a spanking. That's us.

Shuster draws himself as well. A painter stands earlier his sheet, brush in hand, staring at his model (one of the very few women non in high heels). The sketch on the sheet is virtually identical to the bodily model. They are made of exactly the same black-on-white pen strokes. Yoe includes a caption:

"At final he had her posed to his satisfaction."

Source: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/tag/robert-crumb/

Post a Comment for "Crumb Illustration the Family That Lays Together Stays Together"